Definisi

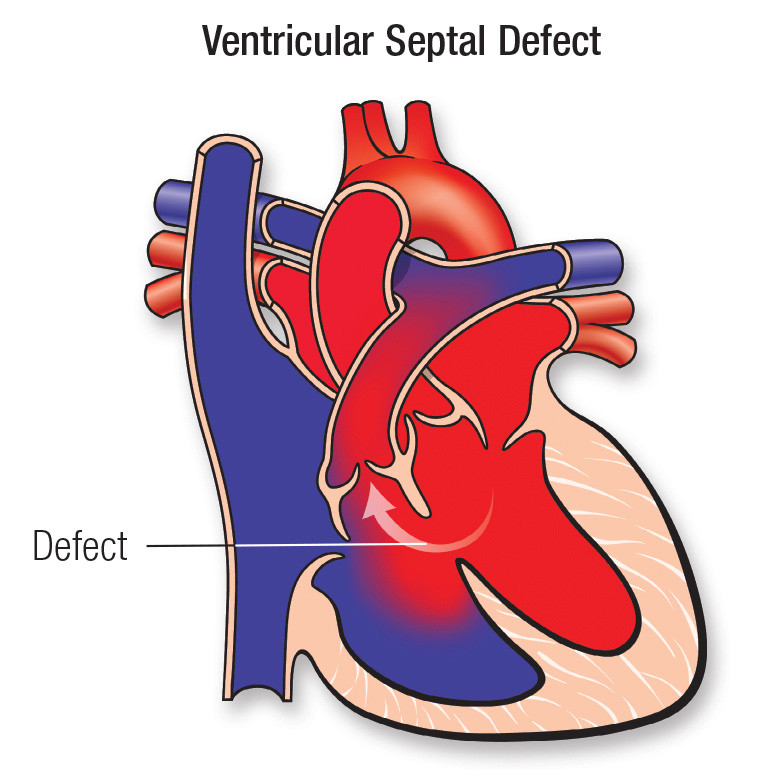

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) merupakan suatu kelainan bawaan di mana terdapat sebuah lubang di antara bilik jantung kiri dan kanan. Lubang (defect) terjadi pada dinding (septum) yang memisahkan bilik bawah jantung (ventrikel) sehingga memungkinkan darah mengalir dari sisi kiri ke sisi kanan jantung. VSD biasanya sudah terjadi selama kehamilan, di mana dinding yang terbentuk di antara kedua bilik jantung tidak sepenuhnya berkembang, sehinggga meninggalkan lubang. VSD termasuk salah satu jenis kelainan jantung bawaan dan sudah ada sejak bayi lahir.

CDC memperkirakan bahwa 42 dari setiap 10.000 bayi yang lahir memiliki VSD. Hal ini berarti sekitar 16.800 bayi lahir setiap tahun di Amerika Serikat dengan VSD. Dengan kata lain, sekitar 1 dari setiap 240 bayi yang lahir di Amerika Serikat setiap tahun lahir dengan VSD.

Bayi dengan VSD dapat memiliki satu atau lebih lubang di tempat yang berbeda. Beberapa lokasi dan nama yang umum dari jenis VSD adalah:

- Conoventrikular Ventricular Septal Defect: Secara umum, lubang jenis ini terjadi pada bagian tepat di bawah katup pulmonal (paru) dan aorta (pembuluh arteri utama).

- Perimembranosa Ventricular Septal Defect, yaitu lubang di bagian atas dinding pemisah (septum) bilik jantung.

- Inlet Ventricular Septal Defect, yaitu lubang pada septum dekat tempat darah masuk ke bilik melalui katup trikuspid dan mitral. Jenis VSD ini juga mungkin merupakan bagian dari kelainan jantung lain yang disebut Atrioventricular Septal Defect (AVSD).

- Muscular Ventricular Septal Defect, yaitu lubang di bagian bawah, bagian otot septum bilik jantung dan merupakan jenis VSD yang paling umum terjadi.

Penyebab

Kelainan jantung bawaan biasanya muncul akibat adanya gangguan pada awal perkembangan jantung, tetapi seringkali tidak diketahui penyebab yang jelas. Genetika dan faktor lingkungan mungkin berperan terhadap timbulnya VSD. Kelainan jantung, seperti VSD dapat terjadi sendiri atau disertai dengan kelainan jantung bawaan lainnya.

Selama perkembangan janin, VSD terjadi ketika dinding otot yang memisahkan jantung menjadi sisi kiri dan kanan (septum) gagal terbentuk sepenuhnya di antara bilik bawah jantung. Biasanya, sisi kanan jantung akan memompa darah ke paru-paru untuk mendapatkan oksigen, sedangkan sisi kiri jantung memompa darah yang kaya oksigen ke seluruh tubuh. VSD memungkinkan darah beroksigen bercampur dengan darah yang oksigennya rendah, sehingga menyebabkan peningkatan tekanan darah dan peningkatan aliran darah di pembuluh darah arteri paru-paru. Hal ini menyebabkan peningkatan kerja pada jantung dan paru-paru.

Faktor Risiko

VSD seringkali terjadi bersamaan dengan kelainan bawaan lahir lainnya. Faktor-faktor yang dapat meningkatkan risiko kelainan bawaan lahir lainnya juga akan meningkatkan risiko terjadinya VSD. Faktor risiko spesifik untuk VSD termasuk:

- Bayi keturunan Asia

- Memiliki riwayat keluarga dengan penyakit jantung bawaan

- Memiliki kelainan genetik lainnya, seperti sindrom Down

Gejala

VSD tidak menimbulkan gejala dalam banyak kasus karena lubangnya tidak cukup besar untuk menimbulkan masalah. Namun, dalam kasus di mana lubangnya cukup besar (atau jika terdapat banyak lubang), hal ini dapat menyebabkan masalah karena kebocoran darah di antara kedua bilik. Ukuran VSD dapat berkisar dari kecil hingga besar, dengan efek yang berbeda-beda, antara lain:

- Kecil (diameter 3 mm atau kurang): Sebagian besar VSD termasuk dalam kategori ini dan tidak menimbulkan gejala. Sekitar 9 dari 10 kasus jenis ini akan menutup dengan sendirinya pada saat anak berusia 6 tahun. Pembedahan untuk jenis ini jarang dilakukan.

- Sedang (diameter 3-5 mm): VSD ini biasanya tidak menimbulkan gejala. Jika mereka tidak menyebabkan gejala atau masalah di tempat lain di jantung dan paru-paru, menunda operasi biasanya disarankan karena pada beberapa kasus juga akan menutup dengan sendirinya.

- Besar (diameter 6-10 mm): VSD ini seringkali memerlukan pembedahan (waktu pembedahan dapat sedikit berbeda). Perbaikan VSD yang besar sebelum usia 2 tahun dapat mencegah kerusakan pada jantung dan paru-paru. Tanpa perbaikan sebelum usia 2 tahun, kerusakan akan menjadi permanen dan dapat memburuk seiring waktu.

Pada bayi, VSD sedang hingga besar menyebabkan gejala yang terlihat seperti gagal jantung, termasuk:

- Sesak napas, termasuk napas cepat atau kesulitan bernapas.

- Berkeringat atau lelah saat menyusui.

- Gagal tumbuh (pertambahan berat badan lambat).

- Infeksi saluran pernapasan yang sering terjadi.

VSD pada anak yang lebih besar dan orang dewasa dapat menyebabkan hal berikut:

- Merasa lelah atau mudah kehabisan nafas saat berolahraga.

- Memiliki risiko sedikit lebih tinggi untuk mengalami radang jantung yang disebabkan oleh infeksi.

- Kulit yang sangat pucat atau kebiruan pada kulit dan bibir (kondisi yang disebut sianosis) dapat terjadi.

Diagnosis

Dalam mendiagnosis VSD, dokter akan mulai dengan melakukan wawancara dengan orang tua atau pengasuh bayi. Dokter akan menanyakan gejala-gejala apa saja yang dialami, sejak kapan gejala muncul, serta mencari kemungkinan adanya kelainan bawaan lahir lainnya. Selanjutnya dokter akan melakukan pemeriksaan fisik, terutama dengan menggunakan stetoskop untuk mendengarkan bunyi jantung bayi Anda. Selain itu, dokter juga mungkin akan melakukan beberapa pemeriksaan penunjang lainnya, seperti:

- Ekokardiogram. Dalam pemeriksaan ini, gelombang suara akan menghasilkan gambar video jantung. Dokter dapat menggunakan tes ini untuk mendiagnosis VSD dan menentukan ukuran, lokasi, dan tingkat keparahannya. Tes ini juga dapat digunakan untuk melihat apakah terdapat masalah jantung lainnya. Ekokardiografi juga dapat digunakan pada janin (fetal echocardiography).

- Elektrokardiogram (EKG). Tes ini akan merekam aktivitas listrik jantung melalui elektroda yang menempel pada kulit dan membantu mendiagnosis kelainan jantung atau masalah irama jantung.

- Rontgen dada. Gambar sinar-X dapat membantu dokter melihat jantung dan paru-paru untuk menilai apakah jantung membesar dan apakah paru-paru memiliki cairan ekstra.

- Kateterisasi jantung. Dalam tes ini, tabung tipis fleksibel (kateter) akan dimasukkan ke dalam pembuluh darah di selangkangan atau lengan dan dipandu melalui pembuluh darah ke jantung. Melalui kateterisasi jantung, dokter dapat mendiagnosis kelainan jantung bawaan dan menentukan fungsi katup dan bilik jantung

- Oksimetri nadi. Sebuah klip kecil akan diletakkan di ujung jari untuk mengukur jumlah oksigen dalam darah.

Tata laksana

Sebagian besar VSD terlalu kecil untuk menyebabkan masalah apa pun, dan kemungkinan akan menutup dengan sendirinya pada usia 6 tahun. Dalam kasus tersebut, dokter kemungkinan akan merekomendasikan untuk tidak melakukan operasi, menyarankan pemantauan gejala dan melihat apakah lubang dapat menutup secara mandiri. Ketika VSD berukuran sedang atau lebih besar, dokter Anda kemungkinan akan merekomendasikan untuk memperbaiki VSD dengan menutup lubangnya. Dua cara utama untuk memperbaiki VSD adalah:

- Pembedahan: Cara yang paling dapat diandalkan untuk menutup VSD adalah dengan menambalnya melalui pembedahan. Untuk melakukan ini, dokter ahli bedah jantung akan mengoperasi dan menambal atau menutup lubang. Dalam kasus lain, mungkin melibatkan tambalan yang terbuat dari bahan sintetis atau cangkok jaringan Anda sendiri.

- Prosedur transkateter: Seperti kateterisasi jantung, prosedur ini menggunakan pendekatan transkateter (berbasis kateter) untuk mengakses jantung melalui pembuluh arteri utama. Setelah perangkat kateter mencapai lubang, ia dapat menempatkan perangkat khusus yang disebut occluder dan menyumbat lubangnya. Perangkat ini biasanya terbuat dari kerangka mesh yang dilapisi bahan sintetis.

Dalam kasus di mana bayi atau anak kekurangan berat badan atau tidak tumbuh pada tingkat yang diharapkan, dokter dapat merekomendasikan tindakan khusus untuk membantu mereka mendapatkan nutrisi yang cukup. Hal ini mungkin termasuk diet khusus atau bahkan penggunaan selang makanan.

Obat dapat mengobati gejala VSD sebelum operasi atau jika VSD cenderung menutup dengan sendirinya seiring waktu. Obat umum untuk VSD seringkali sama dengan obat yang mengobati gagal jantung, termasuk:

- Diuretik: Obat-obatan ini dapat meningkatkan jumlah cairan yang dikeluarkan ginjal dari tubuh Anda.

- Obat gagal jantung: Obat-obatan ini membantu mengontrol kekuatan dan waktu detak jantung Anda. Contohnya adalah digoxin, obat umum dalam pengobatan gagal jantung yang juga berguna untuk VSD.

Komplikasi

VSD kecil mungkin tidak akan menyebabkan komplikasi. VSD yang sedang atau besar mungkin menyebabkan beberapa komplikasi, seperti:

- Gagal jantung. Pada jantung dengan VSD sedang atau besar, jantung bekerja lebih keras dan paru-paru memiliki terlalu banyak darah yang harus dipompa ke jantung. Tanpa pengobatan, kondisi ini akan menyebabkan gagal jantung.

- Hipertensi paru. Peningkatan aliran darah ke paru-paru karena VSD menyebabkan tekanan darah tinggi di arteri paru-paru (hipertensi pulmonal), yang dapat merusaknya secara permanen. Komplikasi ini dapat menyebabkan pembalikan aliran darah melalui lubang (sindrom Eisenmenger).

- Endokarditis. Infeksi jantung ini merupakan komplikasi yang jarang terjadi.

- Masalah jantung lainnya, termasuk irama jantung yang tidak normal dan masalah katup.

Pencegahan

Karena tidak ada penyebab yang diketahui untuk VSD, pencegahan biasanya tidak mungkin dilakukan. Namun, Anda dapat mengurangi risiko dengan menghindari penggunaan alkohol dan mengonsumsi obat antikejang tertentu selama kehamilan.

Kapan Harus ke Dokter

Konsultasikan bayi Anda ke dokter jika mengalami gejala-gejala yang mengarah ke VSD agar dapat dipastikan penyebabnya.

- dr Nadia Opmalina

Beckerman, James. Ventricular Septal Defect. (2020). Retrieved 05 Juni 2022, from https://www.webmd.com/heart-disease/ventricular-septal-defect

CDC. Facts About Ventricular Septal Defect. (2022). Retrieved 05 Juni 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/heartdefects/ventricularseptaldefect.html

Krause, Lydia. Ventricular Septal Defects. (2018). Retrieved 05 Juni 2022, from https://www.healthline.com/health/ventricular-septal-defect

Ventricular Septal Defect. (2021). Retrieved 05 Juni 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ventricular-septal-defect/symptoms-causes/syc-20353495

Ventricular Septal Defects (VSD). (2022). Retrieved 05 Juni 2022, from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17615-ventricular-septal-defects-vsd