Definition

A metatarsal fracture refers to a break in one of the metatarsal bones in the foot. These bones are long and thin, connecting the ankle to the toes, and play a crucial role in maintaining balance when standing or walking.

Each foot has five metatarsal bones, and the most frequently fractured metatarsal bone is the fifth one, which connects to the little toe. This bone accounts for about 50% of all metatarsal fractures.

Metatarsal fractures are the most common foot injury, affecting both men and women of various racial backgrounds. They are particularly common in children, making up 60% of all pediatric foot fractures.

The fifth metatarsal has the highest fracture rate in children, while the first metatarsal (which connects to the big toe) is the least commonly fractured. These fractures are most prevalent in children under the age of five.

Causes

Metatarsal fractures can result from both direct and indirect injuries. Direct injuries are common in industrial workers who may be struck by heavy objects. Indirect injuries occur when the hindfoot and foot rotate while the forefoot remains stationary.

Repetitive stress injuries can also lead to metatarsal fractures, particularly among athletes, with runners being especially susceptible. Metatarsal fractures account for about 20% of all lower limb fractures in athletes.

Common mechanisms of injury that lead to metatarsal fractures include:

-

Falling from a height

-

Sports-related injuries

-

Ankle inversion injuries (when the foot bends inward)

-

Bone crushing injuries, such as heavy objects falling onto the foot or being run over by a motor vehicle

-

Lifting heavy objects

-

Stress fractures from repetitive or strenuous activities

Fractures of the second, third, and fourth metatarsals rarely occur in isolation but are often accompanied by fractures in adjacent metatarsal bones.

Risk Factor

Several factors can increase the risk of developing a metatarsal fracture, including:

-

Athletes

-

Obesity

-

Osteoporosis

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

-

Diabetes

-

Sports involving high-intensity aerobic activities such as jogging, ballet, gymnastics, or weightlifting

Symptoms

Common signs of a metatarsal fracture include:

-

Swelling and pain at the fracture site

-

Uneven skin over the fracture area

-

Pain when bearing weight on the foot

People with a metatarsal fracture will experience pain while walking and will find it difficult to engage in activities that require weight-bearing on the affected foot. The forefoot is usually swollen and tender to the touch. Obvious deformities in the foot are typically only seen in more complex injuries, especially if the toes are dislocated.

Diagnosis

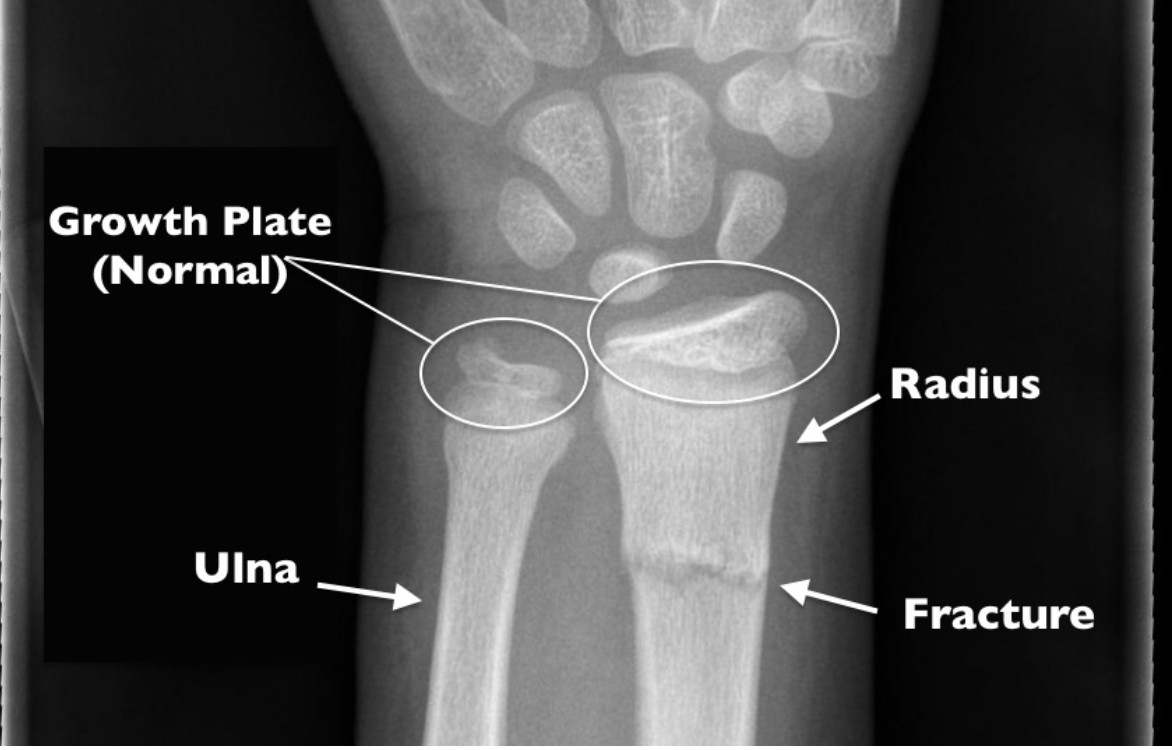

A doctor can often suspect a metatarsal fracture by asking about your injury history and performing a physical examination. After the initial assessment, an X-ray or bone scan will be used to confirm the diagnosis. X-ray is typically sufficient for diagnosing a metatarsal fracture. Meanwhile, CT scan or MRI may be required to rule out other injuries or complications if necessary. A comparison with the opposite foot may also be helpful.

If a stress fracture is suspected due to repetitive activity, a bone scan may be recommended to detect subtle fractures.

The doctor will also examine the nerves and blood vessels around the injury to ensure there is no damage to these structures.

Management

Most metatarsal fractures can be treated without surgery. In uncomplicated cases, wearing a hard-soled shoe, boot, or cast is typically sufficient. The amount of weight you can place on your foot will depend on the type of fracture, and your doctor will guide you on the proper amount of weight-bearing.

The fracture generally takes 8 to 12 weeks to heal, with pain gradually decreasing over time. As the bone heals, you can slowly begin to put more weight on your foot.

If diagnosed with a stress fracture, you will be advised to stop the activity that caused the injury. You should avoid putting weight on your foot for 4 to 6 weeks, or longer, until the pain subsides. Once healed, you can gradually return to your normal activities.

Some metatarsal fractures require surgery. These include:

-

Fractures where bone fragments protrude through the skin

-

Complete fractures where the bone fragments are separated and not aligned, which is common with fractures of the first metatarsal (the bone connected to the big toe)

In these cases, surgery may be necessary to straighten the bone and hold it in place with devices like pins. The pins can usually be removed in 6 to 10 weeks. Sometimes, an incision may be made on the top of the foot to align the bone, and stabilization will be achieved with metal plates and screws.

Special attention is given to fractures near the base of the fifth metatarsal (the protrusion on the outside of the foot), which are called Jones fractures. These fractures are often caused by twisting injuries and can be more common in certain foot shapes. Surgery is typically recommended for athletes or people involved in strenuous physical activities.

After medical therapy, physical therapy should continue to help restore movement and strength. The duration of the treatment depends on the location and severity of the fracture.

The initial phase of physical therapy will focus on range-of-motion exercises that don’t involve bearing weight on the foot. Your therapist will guide you through these exercises to aid recovery.

Complications

Potential complications that can arise from metatarsal fractures include:

-

Metatarsalgia (pain in the sole of the foot due to inflammation)

-

Non-union (when the broken bone doesn't heal together)

-

Mal-union (when the bone heals incorrectly or appears crooked)

-

Delayed union (when the bone heals more slowly than expected)

-

Deformity of the bone

-

Nerve damage in the injured area

Prevention

The risk of metatarsal fractures can be minimized by maintaining a healthy weight and managing any underlying health conditions that may contribute to bone fractures.

Additionally, using proper equipment when engaging in physical activities is essential. Athletes, dancers, or anyone involved in high-intensity activities should always warm up before starting to prevent injuries.

If you experience foot pain after intense exercise, take time to rest to prevent stress fractures. It's also important to wear shoes that provide proper support to avoid injuries.

When to See a Doctor?

If you sustain a foot injury that doesn’t improve with home care, you should consult a doctor immediately. It's also important to seek medical attention if you experience a fever or any of the following symptoms in your foot or leg:

-

Increasing pain

-

Worsening swelling

-

Numbness or tingling

-

Purple or pale skin

If the metatarsal fracture is caused by a severe crushing or twisting injury, the pain is typically intense and will require immediate medical attention. In such cases, go directly to the emergency room (ER) or contact your family doctor.

Looking for more information about other diseases? Click here!

- dr Hanifa Rahma

Metatarsal fractures (no date) Physiopedia. Available at: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Metatarsal_Fractures (Accessed: November 23, 2022).

The Royal Children's hospital melbourne (no date) The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne. Available at: https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/fractures/Metatarsal_Foot_Fractures_-_Emergency_Department/ (Accessed: November 23, 2022).

5th metatarsal fracture: Types, symptoms & treatment (2021) Cleveland Clinic. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22247-fifth-metatarsal-fracture#prevention (Accessed: November 23, 2022).

Agrawal U, Tiwari V. Metatarsal Fractures. [Updated 2022 Sep 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574512/